Sajjad Azhar, senior Pakistani journalist known for his thoughtful storytelling and socio-cultural insights, offers a compelling historical narrative in his recent article on anchient philosopher Kotliya Chanakya published in Independent Urdu. This analysis explores the strengths of Azhar’s article, its narrative power, intellectual framing, and broader value for Urdu readership and South Asian historical discourse.

1. Reclaiming South Asian Intellectual Legacy

At the heart of Azhar’s article is a sincere attempt to reclaim the political and philosophical genius of ancient South Asia, placing Chanakya—also known as Kautilya or Vishnugupta—at the forefront of world political theory. The comparison to Machiavelli is common, but Azhar does not merely mimic this trope; he uses it to assert South Asia’s primacy, emphasizing that Chanakya lived nearly 1,800 years before Machiavelli. This inversion of narrative is decolonial in nature, challenging the Eurocentric canon and reaffirming that deep political thought has flourished independently in the East.

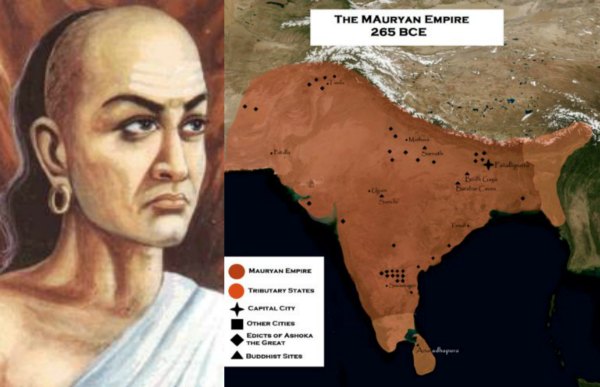

By stressing Chanakya’s birth in Taxila, located near Islamabad, the federal capital of present-day Pakistan, Azhar reclaims geographical as well as intellectual ground. This allows Pakistani readers to see themselves not as outsiders to India’s ancient philosophical traditions, but rather as central inheritors of its political and academic legacy.

2. An Accessible and Engaging Narrative Structure

Sajjad Azhar’s writing is powerful not because it overwhelms the reader with citations or pedantic references, but because it uses accessible language, myth, and chronology to create an engaging historical arc. Starting with a legend—Chanakya being born with teeth and his father removing them to prevent an ominous prophecy—immediately captures attention. Such folklore is not presented as objective fact but as cultural narrative, the kind that builds character mythos in South Asian oral tradition.

Azhar’s smooth movement from Chanakya’s early life to his time at the University of ancient Taxila, known as Takṣaśilā Viśvavidyālaya and then to the political turmoil after Alexander the Great’s invasion, creates a well-structured timeline. He doesn’t burden the reader with academic digressions but rather leads them step-by-step through the transformation of Chanakya from a scholar to a strategist who orchestrated the rise of the Mauryan Empire.

3. Elevating Taxila as a Scholarly Center

One of the article’s most culturally important contributions is its elevation of Taxila as a global intellectual hub of its time. In Pakistan today, the historical significance of Taxila often fades behind modern political concerns. Azhar revives its importance, describing it as a university where politics, economics, medicine, philosophy, military science, and other disciplines were taught—a South Asian Athens, if you will.

This is not just a nostalgic gesture. In doing so, Azhar performs an important cultural service: reinstating local geography in the global imagination of learning. Readers are prompted to recognize the depth of civilization that once existed on their very soil. Such historical reminders help build national pride that is rooted in knowledge and culture, not just politics or conflict.

4. Emphasis on Strategic Wisdom

Azhar portrays Chanakya not merely as a teacher but as a mastermind of statecraft. He references Chanakya’s authorship of the Arthashastra, a treatise that many scholars regard as one of the earliest formal texts on governance, economics, military strategy, and diplomacy. Without turning the piece into a textbook summary, Azhar outlines key themes that made Chanakya unique: pragmatism, use of espionage, alliance politics, and zero-tolerance for injustice.

This representation aligns well with modern political realities, allowing readers to draw parallels between ancient strategic wisdom and contemporary geopolitical decision-making. In a region where political literacy is often shaped by media soundbites, such nuanced portrayals of ancient thinkers as complex, strategic leaders are both refreshing and much needed.

5. Balanced Use of Myth and History

Azhar skillfully blends legendary storytelling with historical credibility, neither becoming overly mythical nor skeptical. For instance, the dramatic tale of Chanakya vowing revenge after being insulted by the Nanda king and later raising Chandragupta Maurya to topple an empire is recounted with energy, but also with journalistic care. He uses qualifying phrases keeping the boundary between history and legend intact.

This technique not only adds flavor to the article but also respects the intelligence of the reader—a rare quality in popular journalism.

6. Political and Cultural Implications

The article resonates beyond biography; it reinforces a regional identity rooted in resilience, intellect, and state-building capability. In an age where narratives of South Asian inferiority often dominate international discourse, Azhar’s piece subtly reminds readers that empire-building, governance, and diplomacy were integral parts of their heritage.

For Pakistani audiences in particular, this is a much-needed cultural revival. It bridges a historical gap—showing that the present-day boundaries were once part of a unified intellectual and civilizational space. It is also a unifying article; Hindu, Buddhist, and secular readers alike can find meaning in Chanakya’s contributions.

7. Potential Areas for Expansion

While the article achieves much, a few areas could be enhanced to further strengthen its impact:

-

Deeper Comparative Analysis: A side-by-side discussion of The Prince and Arthashastra could offer more analytical value, especially for readers curious about political theory.

-

Direct Quotations: Including translated excerpts from Arthashastra would ground the narrative more firmly in primary text.

-

Visual or Interactive Media: Independent Urdu could enhance such features with timelines, maps, or even mini-documents for deeper reader engagement.

However, these are suggestions for enrichment, not criticisms of what is already a solid piece of historical journalism.

8. Why This Article Matters Today

In an era of hyper-nationalism and distorted histories, Sajjad Azhar’s piece provides a grounded, respectful, and well-researched look at a shared past. It’s not only a lesson in history but also a lesson in intellectual humility and curiosity.

It empowers Urdu-language readers to see their history not as borrowed or imported, but as deeply rooted in the global legacy of knowledge. It calls upon young minds to value thought, strategy, and education over conquest and rhetoric.

Sajjad Azhar’s article on Chanakya is more than a biography—it is a celebration of intellectual heritage. Through elegant storytelling, balanced tone, and cultural awareness, he delivers a narrative that educates, inspires, and reclaims South Asian historical identity. Independent Urdu deserves equal credit for providing the platform to publish such high-caliber journalism in Urdu—an essential act in the preservation and propagation of thoughtful historical discourse.

For readers in Pakistan, India, and the Urdu-speaking world, this article is a reminder: our soil has produced visionaries who mastered the art of governance long before modern textbooks caught up. Intrestingly, the writer concluded by highlighting that Indian givernment, in order to acknowledge the genius legacy of Kotliya Chanakya, has named the diplomatic enclave, located at New Delhi, as Chanakyapuri.

Dr. H. Zafar is a distinguished writer and analyst associated with Press Network of Pakistan as Associate Editor. With a strong academic background and years of research experience, she brings depth, clarity, and analytical rigor to her writings.