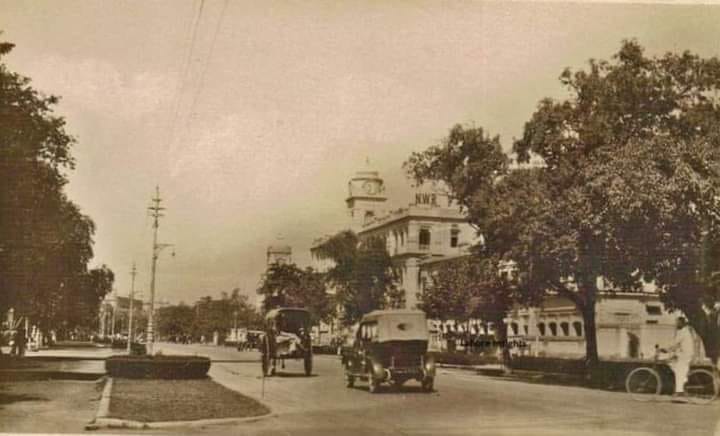

When the British annexed Punjab in 1849 by taking the throne of Lahore from the Sikhs, they inherited not only political power but also a city steeped in centuries of Mughal and Sikh history. Eight years later, in 1857, after crushing the uprising and establishing firm control over Delhi, the British Empire stood unchallenged across much of the Indian subcontinent. With power consolidated, the colonial administration turned its attention to reshaping cities—none more strategically important than Lahore.

Rather than expanding within the dense and symbolic Walled City, the British deliberately developed a “new Lahore” outside its fortification walls. This was not an accidental choice. Broad roads, administrative buildings, cantonments, and European residential areas reflected colonial ideals of order, surveillance, and separation from the native population. The blueprint of this new Lahore still defines the city’s core today, with Mall Road acting as its backbone.

Mall Road: The Spine of Colonial Lahore

The foundation of Mall Road was laid in 1851. Nearly seven kilometers long, it was designed and constructed under the supervision of Lieutenant Colonel Napier, a civil engineer of the British Army. Mall Road was conceived not merely as a road but as a ceremonial and administrative axis. Along it rose some of the most powerful symbols of British authority, including the Governor House, courts, educational institutions, and clubs meant exclusively for Europeans.

From Mall Road, numerous secondary roads branched out, each forming part of a carefully planned urban system. When Lahore Railway Station was established in 1859, it was deliberately connected to Mall Road through a network of roads, reinforcing the importance of railways as the lifeline of colonial administration and trade.

Courts, Commanders, and Colonial Names

Adjacent to the then Chief Court of Punjab—now the Lahore High Court—lies Fane Road. This road was named after Sir Henry Fane, an Irish-born Commander-in-Chief of British India. The naming of streets after military leaders was common practice, serving as a constant reminder of imperial dominance.

Behind the High Court, a smaller street known as Turner Road still exists. It was named after Alweyn Turner, a notable lawyer and judge during the British period. These lesser-known names are equally significant, as they reflect the legal and bureaucratic machinery that sustained colonial rule.

From Exhibition Halls to Electronics Market

Returning to Mall Road, Regal Chowk marks a key junction. From here, Hall Road branches off to the left. Today, Hall Road is synonymous with Lahore’s largest electronics market, bustling with wholesalers and retailers. However, its name originates from four large exhibition halls that once stood there. These halls were used for public exhibitions, trade displays, and official gatherings. Over time, they were demolished and replaced by commercial buildings, but the historical name endured.

Adjacent to Hall Road is Beadon Road, which connects Mall Road to McLeod Road. The road is named after Sir Cecil Beadon, Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, who played a prominent role in suppressing the 1857 rebellion. Like many colonial street names, Beadon Road reflects a narrative of resistance, control, and imperial consolidation.

Charing Cross and the Symbolism of Empire

One of the most iconic colonial landmarks of Lahore was Charing Cross, now known as Faisal Chowk. Modeled after London’s Charing Cross, it once featured a statue of Queen Victoria, symbolizing British sovereignty. The space was designed as a focal point of the colonial city, where major roads converged and imperial power was visually asserted.

Opposite Charing Cross, the road leading toward present-day Qartaba Chowk was known as Queens Road. Named in honor of Queen Victoria, it was lined with residences of British officers and elite families, forming an exclusive European neighborhood.

McLeod Road and the Making of Institutions

Facing the Lahore High Court, another major road branches off Mall Road: McLeod Road. It was named after Sir Donald Friell McLeod, a senior colonial administrator who made lasting contributions to Lahore. McLeod played a key role in the establishment of Oriental College and assembled a significant personal library, which later became part of Punjab University’s collection. He was also instrumental in the development of Lahore Railway Station. The road bearing his name thus reflects both administrative authority and educational legacy.

From McLeod Road, near the historic Lahore Hotel, Nicholson Road branches out toward Empress Road via Qila Gujjar Singh. Nicholson Road commemorates John Nicholson, an Irish officer of the East India Company. Nicholson was one of the most celebrated—and feared—British officers and was killed during the 1857 uprising in Delhi. His name on Lahore’s map remains a reminder of the violent struggles that accompanied colonial expansion.

Empress Road and the Railway Empire

Empress Road was named after Queen Victoria, who was formally proclaimed Empress of India in 1876. This road connected Shimla Pahari to Lahore Railway Station and housed key railway offices and headquarters. The railway network was the backbone of British control, enabling rapid troop movement, efficient administration, and economic extraction. Empress Road symbolized this imperial infrastructure in motion.

Egerton, Flatties, and Elite Life

Egerton Road was named after Sir Robert Egerton, Lieutenant Governor of Punjab. Along this road stands the historic Flatties Hotel, established in 1880 by an Italian entrepreneur, Andrea Flatties. During the colonial era, such hotels were essential for European officers and travelers seeking familiar living standards. Over time, Flatties became one of Lahore’s most prestigious hotels. Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah stayed here, as did international figures such as Marlon Brando and Ava Gardner.

Davis Road, Arts, and Public Spaces

Davis Road connects Shimla Pahari to Upper Mall Road and was named after Sir Robert Henry Davis, Lieutenant Governor of Punjab in 1871. A Welshman by origin, Davis played an important role in shaping Lahore’s cultural landscape. He was instrumental in establishing Lahore Zoo and the Mayo School of Arts, now known as the National College of Arts (NCA), one of Pakistan’s premier art institutions.

Lord Mayo and the Cost of Empire

Lord Mayo, who served as Viceroy of India from 1869 to 1872, also left a lasting mark on Lahore through Mayo Hospital. His real name was Richard Southwell Bourke, the sixth Earl of Mayo from Ireland. His career ended dramatically when he was assassinated during a visit to the Andaman Islands by an Afridi Pashtun prisoner. His death underscored the simmering resentment and resistance that persisted beneath the surface of colonial rule.

A City of Roads, A City of Memory

Beyond these major arteries, Lahore is dotted with roads named after British officers and administrators: Chamberlain Road, Brandreth Road, Montgomery Road, Cooper Road, and Lawrence Road. Lawrence Garden—now Bagh-e-Jinnah—also carries the legacy of Sir John Lawrence, Chief Commissioner of Punjab.

Together, these roads form a living map of Lahore’s colonial past. Even as many names have changed and new identities have emerged, the physical layout of British Lahore remains deeply embedded in the city. Each road tells a story—not just of development and modernity, but of power, resistance, and transformation. To walk through Lahore today is to move through history, where the past continues to shape the present in brick, stone, and asphalt.

Muhammad Iqbal Harper is a Lahore-based senior journalist. He is also President of Pakistan Sports Federation.