1948: UN invention records multiple languages

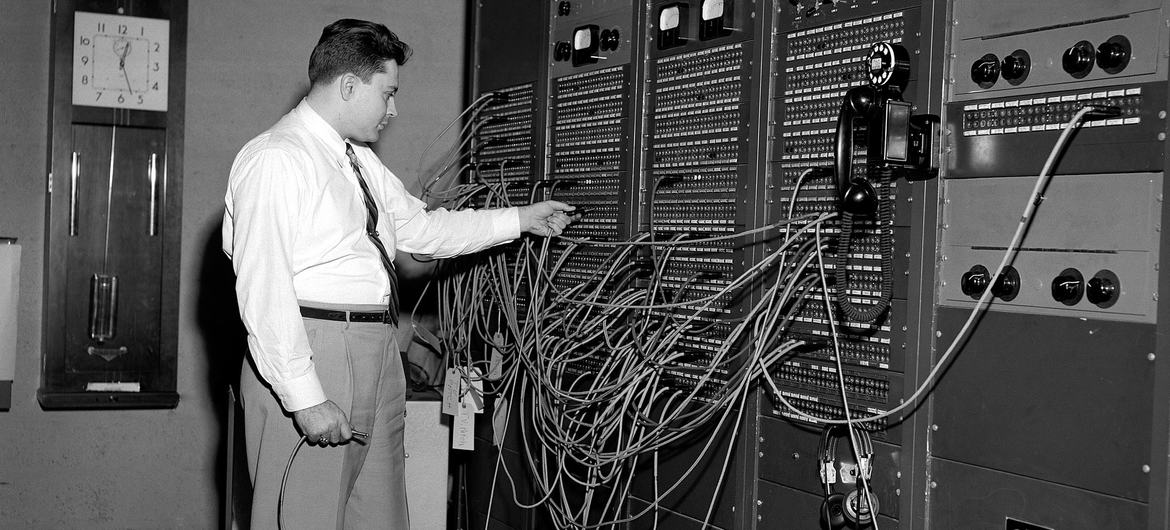

Precision, speed and accuracy were the hallmark of a brand-new machine the UN developed and deployed in 1948 to record multilingual meetings.

At the time, note takers hired to cover the meetings had to pass a 200-words-a-minute test. Alas, human beings are only human and could suddenly become ill or simply miss a word in the heat of a debate.

Enter a new-fangled device (pictured above).

Adapted from traditional recording equipment, it produced an automatic soundtrack capturing even the fastest spoken words in multilingual meetings.

The end product: a vinyl album that could then be referred to, if necessary, for verification purposes.

A meeting in progress is routed to a radio station by a double plug system (shown here) – one line carrying the meeting, or the interpretation, into the transmission board, the other carrying it out by telephone wire. (file)

1950s: Live from New York, it’s the UN!

Producing news in as many as 25 languages daily during the mid-20th century, UN Radio would also broadcast and record official meetings at UN Headquarters.

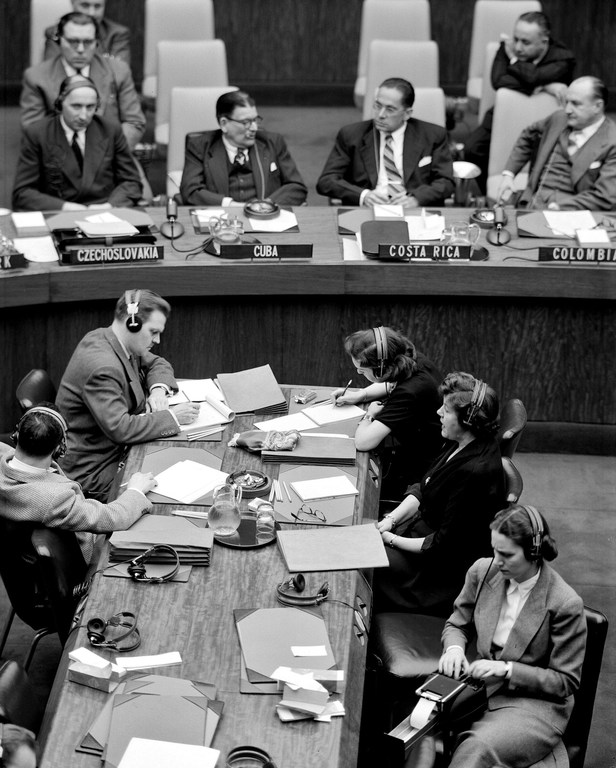

Precis and verbatim reporters and press officers cover a First Committee meeting. (file)

Using modern (at the time) equipment, a dedicated team would monitor a meeting in progress, routing it to a radio station with a double-plug system (shown in the photo above).

One line carried the meeting – or the interpretation, depending on the language required – into the transmission board, and another carried it out by telephone wire to the station.

1950s: Every word stenotyped

In the meeting rooms, précis and verbatim writers alongside Meetings Coverage press officers were hard at work.

Skilled fingers raced silently over the keys of the latest stenotype machines or stenographers’ pads.

Every word was taken down on paper, both the original speech and its interpretation.

As members of the most highly qualified corps of verbatim reporters, many of these men and women had years of experience at international conferences, often with a League of Nations background.

1951: The lid is off

Once finalised, a document was ready for printing.

When the UN Secretariat opened for business at UN Headquarters in New York in 1951, an on-site print shop filled a large portion of the sub-basement with its gigantic printing presses, typesetting stations and other specialised publishing equipment.

A typesetter at work at UN Headquarters. (file)

The head of bookbinding at the Reproduction Unit, William L. Watson, helped to develop a new binding technique in 1952.

Typesetters started the day opening up large flat boxes containing tiny metal replicas of the alphabet and punctuation marks in various fonts, similar in size to manual typewriter letter strikers.

At the end of each day, the last typesetter working replaced the closed the boxes to protect the contents from dust before calling up the UN Spokesperson’s Office to report that “the lid is on”.

The phrase made its way into the UN Spokesperson’s Office daily announcements on the Secretariat intercom system, telling the press, staff and delegates alike that the day was done, with no official statements expected to be printed.

Head of bookbinding at the Reproduction Unit, William L. Watson demonstrated a step in a new technique he helped to develop in 1952. (file)

1960s: Hot off the press

From the minute words were recorded on paper, assistants would run the paper to editors via pneumatic tubes installed throughout the building.

UN Headquarters provides the most modern technical facilities to make the meetings, some conducted in five languages, intelligible both to participants and to visitors, and to make the proceedings available to listeners, viewers and readers. (file)

In addition, tiny dumb-waiter elevators that could accommodate several stacks of documents were embedded on certain floors as a quick link to and from the print shop to such offices as the Meetings Coverage Section and the UN Spokesperson’s Office for priority documents like the Secretary-General’s statements, daily summaries and press releases.

Journalists found these materials on specially made mid-century metal racks – that remain to this day – on the second floor of the UN Secretariat.

In various rooms and chambers, delegates visited conference officers at their built-in counters to collect the latest draft resolutions and records of former proceedings, or if they needed such items as pencils, note paper and ashtrays.

2012: Printing eliminated

While the frantic process of covering meetings largely remains the same today, the UN has adapted into the 21st century with ever newer technology and innovations.

Almost 80 years later, there are no ashtrays in conference rooms, and computers and the internet replaced the need for dumb-waiters, which were removed, and have helped to eliminate the rush or demand for printed material.

When Hurricane Sandy hit New York in 2012, flooding damaged much of the UN print shop, which then downsized when the world was already advancing towards sustainability.

Many documents were no longer printed in large quantities and instead were posted on UN websites.

Same mission in the 21st century: Precision, speed and accuracy

The Department of Global Communications, though it got a new 21st century name to replace its original one – Department of Public Information – still relies on the same 20th century mission: precision, speed and accuracy.

Journalists now can find informal summaries of meetings online shortly after a meeting ends or follow breaking UN news on social media platforms like X, formerly Twitter, in 10 languages – Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Hindi, Portuguese, Russia, Spanish, Swahili and Urdu.

UN staff covering meetings can still verify their work, not on vinyl or audio cassettes produced hours after the gavel sounds, but instantly via UN WebTV.

Adapting itself during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns that shuttered the Secretariat in 2020, UN WebTV now broadcasts all official in-person and virtual meetings live and on-demand online in the UN’s six official languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish), also available on the UN’s YouTube website.

Staffan de Mistura, UN Special Envoy for Syria, seen leaving the Security Council Stakeout area after briefing journalists following a meeting of the Security Council on the situation in that country. (file)

Lingering history at UN Headquarters

Some history lingers at the UN Secretariat even today.

“The lid is on” did, even when the printing presses fell silent, and boxes of typesetting letters were retired. UN News named its flagship podcast series after the phrase, which still resonates via the second-floor UN Spokesperson’s Office intercom announcements as a cherished beacon to mark the end of the work day.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of decades-old official documents have been digitised thanks to the UN Dag Hammarskjöld Library and the UN Audiovisual Library, from the longest ever speech delivered at the General Assembly to the Security Council resolution adopted to recognise the State of Israel.

Catch up on UN Video’s Stories from the UN Archive episodes here, and follow our accompanying series here. Join us next week for another dive into history.

And with that invitation, the lid is on.

UN Meetings Coverage press officers in the Security Council Chamber summarised a debate on Syria in 2016. (file)